Honoring Memory: My Motivation for Telling This Story

By Dave Heuring

When I began writing my autobiography in the summer of 2024, one of my first questions was simple: why was I born in Lansing, Michigan? My parents had moved there shortly after Dad returned from the Korean War, and I wondered if his service might have something to do with it. But I knew very little about that chapter of his life. I happened to have a copy of his DD-214 discharge document, and on impulse, I entered his unit designation into a Google search. What appeared on my screen surprised me: accounts of the so-called "Forgotten War" and the Battle of the Frozen Chosin—which for the first time I realized was the battle Dad had been in, one he had spoken of just a few times during my childhood.

I then contacted my youngest brother, Fuff, who shared what he had learned about Dad's war experience after he passed away. Our conversation revealed just how much we didn't know about what our father experienced at Chosin. He particularly wanted to know whether Dad had escaped across the ice or along the shoreline when the convoy was abandoned. Intrigued, I set aside my autobiography and spent the next three weeks completely immersed in learning everything I could about the Battle of the Frozen Chosin.

I conducted extensive research on the battle, reading books, watching YouTube videos, and eventually retrieving decades-old documents from the National Archives. What I uncovered left me both stunned and filled with a quiet sadness for what Dad had endured. From this research, I have compiled an account of Norman Heuring's experience at the Battle of the Frozen Chosin—a tribute to give him the respect and recognition he deserves, even if it comes too late. I have prepared this account for my brothers and sisters and their families, so that they too will know what our father survived and carried with him all those years.

As you will read, the battle was horrific and ended with the destruction of the task force to which he belonged. Dad served in Company K, 3rd Battalion, 31st Regiment, 7th Infantry Division. His company commander, Captain Robert J. Kitz, survived and later wrote a seven-page personal statement describing the ordeal. His account, as well as many other sources, provided me with a deeper understanding of the unimaginable hardships, acts of bravery, and the true sequence of events that unfolded during those desperate days.

The Hidden Truth

Unfortunately, serious mistakes made by senior officers at the highest levels of command led to the aftermath being shrouded in secrecy: all Army records from the battle were stamped "secret" and sealed for 50 years, concealing the true story of what happened during those four days and five nights of desperate fighting.

(2,500 Americans, 700 ROK)

Of the original 3,200 men in this regimental task force—comprising 2,500 Americans and 700 Republic of Korea (ROK) soldiers—Dad was one of only 385 able-bodied survivors. Yet he and the others were unjustly labeled as having abandoned their positions and fled. I have to wonder if this accusation weighed heavily on him for the rest of his life. It is deeply regrettable that the truth of what this task force endured only emerged many years later, after historians pieced together an accurate account based on interviews with survivors and declassified documents from the National Archives. This account draws heavily on the scholarly work of military researcher Roy E. Appleman, among other sources.

Reference: Appleman, Roy E., East of Chosin: Entrapment and Breakout in Korea, 1950.College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 1987.

Sadly, Dad passed away in 1998, never knowing that the world would one day recognize the true significance of his task force's sacrifice. The four-day, five-night stand by the task force played a critical role in holding back the Chinese army, preventing them from closing the only escape route to the port at Hungnam. Without their resistance, the Chinese forces could have cut off and destroyed X Corps—consisting of the 1st Marine Division and elements of the 7th Infantry Division—as they fought their way south from the western and eastern shores of the Chosin Reservoir.

The Origins and Early Course of the Korean War

The Korean War began in the context of post-World War II tensions and the emerging Cold War. After Japan's defeat in 1945, Korea was divided at the 38th parallel: the Soviet Union occupied the north, and the United States the south. This division, intended as a temporary administrative measure, soon became permanent as both sides established rival governments—communist in the North under Kim Il Sung, and anti-communist in the South under Syngman Rhee.

The Invasion: June 25, 1950

In January 1950, U.S. Secretary of State Dean Acheson delivered a speech outlining America's "defensive perimeter" in the Pacific, notably omitting South Korea from the areas the United States would automatically defend. Many historians believe this omission contributed to North Korean leader Kim Il Sung's decision to launch an invasion, under the assumption that the United States would not intervene militarily.

On June 25, 1950, North Korea launched a full-scale invasion of South Korea, aiming to reunify the peninsula by force. North Korean forces, well-equipped with Soviet tanks and artillery, quickly overran South Korean positions, capturing Seoul within days. The United Nations, led by the United States, responded by sending military forces to support South Korea. Despite this intervention, by August, South Korean and UN forces were driven back to a small defensive perimeter around the port city of Pusan, where they made a determined stand against further North Korean advances—an area that became known as the Pusan Perimeter.

The Inchon Landing and Northern Advance

In September 1950, UN forces launched a bold counteroffensive that dramatically shifted the course of the Korean War. Under the command of General Douglas MacArthur, they executed a daring amphibious landing at Inchon, striking far behind North Korean lines. This surprise operation enabled UN troops to break out from the Pusan Perimeter, swiftly recapture Seoul, and force the North Korean army into a rapid retreat.

Following this success, UN and South Korean forces advanced northward, crossing the 38th parallel and pushing deep into North Korea, reaching various points along the Yalu River near the Chinese border by late October. During this advance, key units including the 1st Marine Division and elements of the 7th Infantry Division moved into the rugged terrain around the Chosin Reservoir, setting the stage for one of the war's most intense and challenging battles.

By late October 1950, UN forces approached the Yalu River, Korea's border with China. General Douglas MacArthur and other U.S. leaders, confident in the rapid progress, assured the public that the war would soon be over. Despite warnings from Beijing, the advance continued. In late October and early November, Chinese forces entered the war, launching massive attacks against the advancing UN troops. This intervention caught the UN forces by surprise and quickly shifted the momentum of the conflict. By November, UN troops in northeastern Korea, including those around the Chosin Reservoir, faced not only vastly increased numbers of Chinese troops, but also a new and dangerous enemy in the bitter cold of the Korean winter.

Dad had previously served a year and seven months in the U.S. Army at stateside camps before being discharged and placed on reserve status. After the Korean War erupted, he was ordered to report for a physical exam on September 18, 1950, after which he was recalled to active duty. He likely arrived in Korea in early or mid-November 1950, joining Company K of the 31st Infantry Regiment. At that time, his regiment was deployed in northeastern North Korea and had received orders to relocate to the Chosin Reservoir to relieve marine units on the eastern side of the reservoir. Dad joined his unit during this relocation, as Company K prepared for what was planned as a final push northward to the Chinese border.

We don't know the actual date that he joined his unit in Korea. We know he was reactivated in mid-September and then posted at Fort Lewis in Washington state awaiting orders to relocate to Korea. He was most likely sent by ship from Fort Lewis to Pusan, Korea—typically a 30-day trip—so a best guess is that he arrived there in mid-November. In an effort to clarify this, as well as to learn more about Dad's complete military service, I contacted the National Personnel Records Center and requested his service file. Unfortunately, I learned that a fire in July 1973 had destroyed many records, including his—a significant disappointment, as I had hoped to uncover much more about both his initial service and his wartime experience. The only documents I received were his reactivation orders and his final discharge papers.

The Battle of Chosin Reservoir

Strategic Context and Command Decisions

By late November 1950, the stage was set for one of the most brutal confrontations of the Korean War. UN forces, confident from recent victories, were unprepared for what awaited them at the Chosin Reservoir. In the aftermath of the successful Inchon Landing and the rapid advance northward, General Douglas MacArthur and the X Corps command remained convinced that Chinese intervention would be limited. Intelligence reports warning of large Chinese troop movements were largely dismissed or downplayed. MacArthur's headquarters maintained that any Chinese forces in Korea were merely volunteers in small numbers, not a coordinated military intervention.

This miscalculation had dire consequences. General Edward Almond, commanding X Corps, ordered his forces to continue their advance toward the Yalu River despite mounting evidence of massive Chinese presence. The 1st Marine Division was positioned on the western side of the Chosin Reservoir, while Regimental Combat Team 31 (RCT-31) from the 7th Infantry Division was deployed on the eastern shore. These forces were separated by the frozen reservoir and connected only by a treacherous mountain road.

The orders that sent RCT-31 into position reflected a fundamental misunderstanding of the tactical situation. The regiment was spread thin across multiple positions along the eastern shore, with units separated by significant distances and difficult terrain. This dispersion would prove catastrophic when the Chinese attack came.

The Opposing Forces

By November 27, Chinese Communist Forces had quietly maneuvered into position around the Chosin Reservoir. The 80th and 81st Divisions of the Chinese 27th Army occupied the high ground completely surrounding the American positions. These were experienced, battle-hardened troops who had fought in the Chinese Civil War. They were equipped for winter warfare and trained in night operations and infiltration tactics.

The Chinese numbered approximately 60,000 troops around the Chosin Reservoir, with additional divisions in supporting positions. Against this force, RCT-31 on the eastern side of the Chosin Reservoir could field approximately 3,200 men, including 2,500 Americans and 700 Republic of Korea soldiers—facing odds of nearly 19:1. The Marines on the western side had greater strength of around 7,000 troops plus support units, but were also heavily outnumbered at approximately 9:1.

The temperature on November 27 dropped to −25°F, with wind chill driving it even lower. These conditions affected everything—weapons froze, vehicles wouldn't start, medical supplies became unusable, and frostbite became as dangerous as enemy fire. The Chinese, better prepared for winter operations, used these conditions to their advantage, launching attacks during the coldest parts of the night when American defensive capabilities were most compromised.

Task Force MacLean (Later Task Force Faith)

The Army units positioned east of the Chosin Reservoir were organized as Regimental Combat Team 31 (RCT-31), commanded by Colonel Allan D. MacLean of the 31st Infantry Regiment. The task force included elements from multiple units of the 7th Infantry Division. When Colonel MacLean was killed in action on November 29, command passed to Lieutenant Colonel Don C. Faith Jr., commander of the 1st Battalion, 32nd Infantry Regiment (1/32), and the unit became known as Task Force Faith.

The main elements of RCT-31 included:

- 1st Battalion, 32nd Infantry Regiment (1/32)

- 2nd Battalion, 31st Infantry Regiment (2/31)

- 3rd Battalion, 31st Infantry Regiment (3/31)

- 57th Field Artillery Battalion

- Company D, 10th Engineer Combat Battalion

- 31st Tank Company

- Headquarters and Service Company elements

- Republic of Korea (ROK) soldiers attached to various units

Dad served in Company K, part of the 3rd Battalion, 31st Infantry Regiment (3/31), which was commanded by Lieutenant Colonel William R. Reilly.

RCT-31 was deployed in three main perimeter positions along the eastern shore of the Chosin Reservoir, stretched across approximately seven miles. These positions, from north to south, were: the northern perimeter (held primarily by 1/32 Infantry), the 3/31 perimeter at the inlet (where Company K was positioned), and the southernmost perimeter at Hudong-ni, where the RCT-31 rear command post was located. This dispersion across difficult terrain with limited communication between positions would prove to be a critical vulnerability when the Chinese attacked.

The Significance of RCT-31's Position

RCT-31's deployment on the eastern shore of the Chosin Reservoir was part of X Corps' overall strategy to advance to the Yalu River. However, the regiment's position exposed it to several critical vulnerabilities:

- It was separated from the 1st Marine Division on the western shore by the frozen reservoir, making mutual support difficult.

- The only route of withdrawal was a single, narrow mountain road running south through Hudong-ni to Hagaru-ri, approximately 12 miles away.

- The surrounding mountains provided ideal positions for Chinese forces to observe and attack the American positions.

- The dispersed nature of the three perimeters made coordinated defense challenging and prevented units from supporting one another effectively.

Despite these vulnerabilities, RCT-31 was ordered to continue preparations for an attack northward. X Corps leadership under Major General Edward Almond, operating from the port city of Hamhung, followed orders from higher command and maintained an offensive posture even as intelligence reports suggested large-scale Chinese presence in the area. This offensive focus left the task force inadequately prepared for the massive defensive battle that was about to begin.

On the morning of November 27, Colonel MacLean issued Operations Order O-25, directing RCT-31 to 'attack without delay north from Chosin Reservoir' to seize a series of objectives (designated A through E) and prepare to continue the attack to seize Changjin and ultimately reach the Yalu River. The order emphasized: 'Exert utmost energy to surmount weather and terrain conditions' and 'Exploit to maximum the superior capabilities of our troops and equipment.'

Reference: Operations Order O-25, RCT 31, 27 November 1950, Korea 1:50,000 map series.declassified under Authority NND 745074, National Archives.

The 1/32 Battalion was ordered to seize Objective B, the 3/31 Battalion to seize Objective A and protect the regiment's eastern flank, while the 2/31 Battalion (still not deployed at the resevoir) and the 31st Tank Company were ordered to close on Objective A and prepare to attack north. That same evening, at 2200 hours—just hours after this aggressive attack order was issued—the Chinese 80th and 81st Divisions launched their massive assault that would shatter these offensive plans and nearly destroy the entire task force.

Deployment of RCT-31's Units on November 27, 1950

Colonel MacLean deployed his RCT-31 forces from north to south in the following order: 1/32 Infantry Battalion, MacLean's forward command post, 3/31 Infantry Battalion, the 57th Field Artillery Battalion (FAB), the 31st Heavy Mortar Company, medical and food services, a central command post, and finally the RCT-31 rear command post (CP) and 31st Tank Company at Hudong-ni.

The dispersed deployment of the 31st Infantry Regiment on November 27 reflected a fundamental vulnerability. As later command reports documented, the regiment was 'dispersed over 120 road miles apart,' making coordinated operations nearly impossible. The 2/31 Battalion remained at Pungsan 120 miles away, while other elements of the regiment were scattered across northeastern Korea. This dispersion meant that when the Chinese attack came, the two army battalions on the eastern side of the reservoir fought in isolation, unable to receive reinforcement from other regiment elements.

Reference: Headquarters, 31st Infantry, Command Report: 1–4 December 1950,, dated 10 March 1951; declassified under Authority NND 745074, National Archives.

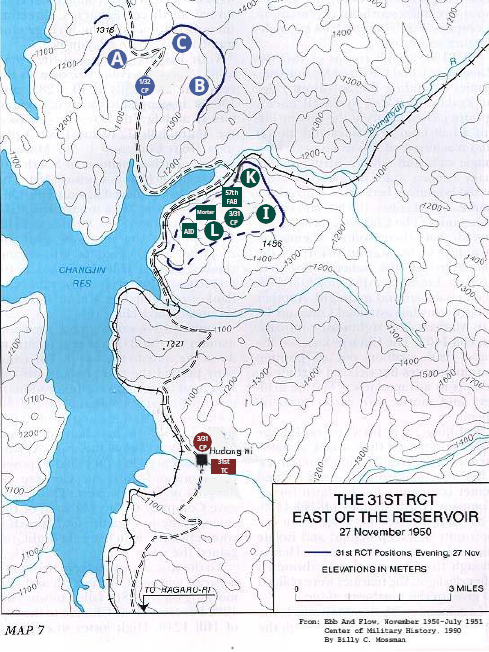

The map below illustrates the deployment of RCT-31's forces. On the reservoir's eastern flank, the regiment's two infantry battalions held strategic positions. Lieutenant Colonel Faith's 1/32nd Battalion secured the northern sector above an inlet that feeds into the reservoir. This battalion relieved Marine units on November 25, allowing those Marines to relocate to the reservoir's western side. Within the 1/32nd, Companies A, B, and C were entrenched in foxholes arranged in an inverted "U" shape, with the forward (CP) situated at the formation's center. When Colonel MacLean arrived on November 27 with other RCT-31's elements, he joined Lieutenant Colonel Faith at the 1/32nd's command post, consolidating the task force's leadership and control of the northern sector.

Task Force MacLean's Positions on November 27

Enhanced from Roy E. Appleman, “31st RCT Positions, 27 November 1950” (Map 7), inEast of Chosin: Entrapment and Breakout in Korea, 1950 (College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 1987).

The 3/31st Battalion arrived on November 27 and comprised Companies I, K, and L, establishing a circular defensive perimeter on the eastern side of the inlet. Dad, serving with Company K, was assigned to one of its three platoons situated in the sector overlooking the bridge spanning a small river at the inlet's tip. At that point, a gravel road from the 1/32nd northern position intersected southbound railroad tracks, which ran in front of the bridge and then followed the reservoir's shoreline south to Hill 1221. While the rifle companies formed the outer ring of the perimeter, the battalion's support elements—the 57th Field Artillery Battalion (FAB), D Company's mortar section, and medical and mess units—were stationed in the protected interior near the battalion's command post.

Further south beyond Hill 1221 lay the third position, located in the modest town of Hudong-ni. Here the RCT-31 rear command post was situated in a schoolhouse with other officers and approximately 100 enlisted soldiers. In addition to the rear CP, the 31st Tank Company and the 31st Medical Company were initially positioned at Hudong-ni with orders to join the deployments further north.

The gravel road that ran from the northernmost position (the 1/32nd Battalion) along the shoreline past the 3/31st perimeter turned away from the parallel railroad at Hill 1221, looped around the opposite side of the hill, and entered Hudong-ni. This road served as the sole means of ingress and egress for the entire area. From Hudong-ni, the road continued another five miles south to Hagaru-ri, where the 1st Marine Division established its forward headquarters and supply base beside a newly constructed airstrip. That strip accommodated Marine aircraft that provided close air support to the Marine units on the reservoir's western shore and to MacLean's RCT-31 on the eastern side. The airfield would later prove critical for evacuating thousands of wounded during the battle.

Basic defensive positions were established, but because the Americans did not anticipate immediate enemy action, they failed to create a tight perimeter, leaving sizable gaps between the three deployments. The situation deteriorated when the Chinese sent the 242nd Regiment of the 81st Division to seize Hill 1221, an undefended hill that controlled the road to Hudong-ni. This move isolated the 31st Tank Company, 31st Medical Company, and rear command post at Hudong-ni from the two main infantry elements to the north—the 1/32nd and 3/31st Battalions—a development that proved decisive in the ensuing battle.

On November 27, the 31st Medical Company followed orders to relocate to where the 3/31st was deployed. After the column moved through the rear command post area at Hudong-ni and continued north, it was ambushed at Hill 1221 by what was estimated to be approximately a company of Chinese forces. The Medical Company was effectively destroyed in the attack—only three or four men managed to fight their way back to the rear CP that night. This devastating ambush not only eliminated the unit but also closed off the road between Hudong-ni and the forward infantry battalions, isolating the 31st Tank Company and rear command post from the main fighting elements to the north.

According to an after-action report by Major Robert E. Drake, Commander of the 31st Tank Company, on November 28 the Tank Company attempted to relocate to the 3/31st location but was repelled by the same CCF units that had destroyed the 31st Medical Company the day before. The following morning, November 29 at 0800 hours, a second and larger relief attempt was mounted with the 2nd, 3rd, and 4th Platoons of the Tank Company, reinforced by a platoon from C Company, 13th Engineer Battalion, the anti-tank mine platoon, and a composite platoon from Headquarters Company, 31st Infantry.

Once again, the column reached intermediate objectives, but overwhelming enemy numbers—now estimated at two battalions well dug in—caused devastating infantry casualties. The acting commander at the rear command post ordered withdrawal back to Hudong-ni. These failed relief attempts left a grim trail of charred, burned-out tanks littering the road around Hill 1221, tanks that would obstruct and eventually need to be passed by Task Force Faith's breakout attempt on December 1.

Reference: Robert E. Drake, Operations Summary, 25 November to 11 December 1950, Tank Company, 31st Infantry Regiment, 12 December 1950, National Archives.

Timeline of the Five-Day Battle

November 27 – December 1, 1950

The following timeline presents a chronological account of the key events during Task Force MacLean/Faith's five-day stand at the Chosin Reservoir. It traces the mounting pressure from overwhelming Chinese forces, the steady erosion of combat power under relentless attacks and extreme cold, and the cascade of command decisions made under fire. Together, these events culminated in the December 1 breakout attempt and the near-total annihilation of Regimental Combat Team 31 (RCT-31).

The first night's Chinese assault began with a ferocious surprise attack under cover of darkness. Bugles sounded and troops shouted as the CCF 80th and 81st Divisions moved to encircle the three deployment positions of Task Force MacLean. The initial blows fell on Faith's 1/32 Infantry Battalion along the northern perimeter, where successive waves pressed steadily closer. By 0030 hours, a coordinated assault broke through Company B's outposts. Company A on the left flank was also completely overrun before being retaken in a counterattack.

During the same night, the 3/31st Battalion faced a ferocious, sustained assault, with Chinese forces breaching the perimeters of all three companies. Company K—our father’s unit—had three platoons stationed along the road in front of the bridge at the inlet’s mouth, but multiple waves of attackers overwhelmed these positions, forcing many riflemen to retreat into the central sector defended by Battery A of the 57th Field Artillery Battalion, which was itself under direct attack. As Battery A was pushed back to join Battery B, the sudden collapse threw the defenses into chaos, and in the confusion, the 57th’s guns accidentally fired into retreating American positions.

At first light, Chinese forces pulled back into the surrounding hills to escape Marine air strikes, leaving behind only sporadic sniper fire. This lull allowed riflemen to return to their foxholes and reestablish a tightened defensive perimeter, consolidating what remained of the force. The battalion command post, though still functioning, had survived a night of brutal close-quarters fighting. The cost was staggering. One platoon from Company K and another from Company I, positioned on neighboring hills, had been completely overrun. Lt. Col. William Riley, commanding the 3/31st Battalion, was seriously wounded, as were many other officers. Casualties reached catastrophic levels: the 1/32nd Battalion lost more than 100 killed and another 100 wounded, while the 3/31st Battalion and the 57th Field Artillery Battalion also suffered severe losses. Inside the perimeter, the ground was strewn with the bodies of both American and Chinese dead.

The second night of CCF assaults began early, but the 3/31st Battalion was better prepared this time, supported by more accurate and sustained 40 mm fire from the 57th Field Artillery that disrupted Chinese assault waves and helped defenders seal most perimeter breaches, though enemy pressure continued relentlessly throughout the night. In contrast, the 1/32 Battalion remained isolated without artillery support, relying solely on rifle companies and limited ammunition. They fought courageously against repeated attacks, suffering increasingly heavy casualties as the wounded mounted and supplies dwindled.

Recognizing how dangerously exposed the 1/32nd Battalion had become, Colonel MacLean ordered it to withdraw south and merge with the 3/31st perimeter, with strict instructions that no weapons or wounded be left behind. Unusable vehicles were destroyed, and surviving casualties were loaded onto every available truck. The column waited until 0500 hours, when first light allowed Marine aircraft to provide overhead protection for the exposed movement south. More than 100 soldiers killed in the previous fighting remained on the battlefield, a stark reminder of the cost already paid.

Under heavy enemy fire, the 1/32nd Battalion fought its way toward the 3/31st perimeter. As the convoy reached the edge of the position, Colonel MacLean made a fatal misjudgment, mistaking a group of Chinese troops for the long-delayed 2/31st Battalion. Convinced that his men were being struck by friendly fire from the 3/31st, he ran toward what he believed were American positions. Instead, he was shot multiple times, captured by Chinese forces, and later died in captivity. With MacLean lost, Lieutenant Colonel Faith of the 1/32nd Battalion assumed command of the combined American force, thereafter known as Task Force Faith.

Lieutenant Colonel Faith consolidated the battered remnants of the various units into a single, more defensible position, reorganizing companies and establishing a tighter perimeter that could be held with reduced numbers. Throughout the day, Marine aircraft provided crucial close air support, strafing Chinese positions in the surrounding hills while conducting vital supply drops of ammunition, medical supplies, and rations to the desperate defenders below. Despite the dangers, search parties ventured out multiple times attempting to locate Colonel MacLean, but all efforts proved fruitless.

Having failed to destroy Task Force MacLean/Faith despite two nights of ferocious, near-continuous assaults, the Chinese forces allowed the third night to settle over the perimeter as an uneasy and deeply deceptive lull. The massed infantry attacks that had battered the lines fell silent, replaced by intermittent bursts of small-arms fire and occasional probing mortar rounds that kept defenders tense and sleepless. This pause was not a retreat but a calculated operational pause, as Chinese commanders regrouped shattered units, shifted forces into more favorable positions, and funneled additional mortar teams and heavier weapons through the narrow mountain passes in preparation for renewed action. The quiet offered no real relief—only the ominous sense that something worse was being assembled in the darkness beyond the hills.

During daylight, Marine transport aircraft attempted to resupply Task Force Faith, but strong winds and poor visibility caused many critical supply drops—including those with 105mm artillery shells, medical gear, and rations—to drift into Chinese-controlled territory, further straining the task force’s dwindling resources. Major General David Barr arrived by helicopter to inform Lieutenant Colonel Faith that RCT-31 would need to withdraw to the 1st Marine Division headquarters at Hagaru-ri. Now under Marine operational control, Task Force Faith would have to fight its way out overland while carrying more than 600 wounded. Marine battalions on the west side of the reservoir were also ordered to prepare for withdrawal, marking a perilous retreat for both Marines and Army forces.

At 1600 hours on November 30, orders sent the 31st Tank Company and RCT-31 rear command post to withdraw from Hudong-ni to Hagaru-ri; the tank company arrived by 1730 hours and was immediately attached to the 1st Tank Battalion, 1st Marine Division. That night brought the fiercest Chinese assault yet, as enemy forces reinforced with heavy mortars and light artillery pounded the 3/31st perimeter without pause until dawn. Barrages of all calibers, up to 120mm, rained on American positions while the task force's own artillery, nearly out of ammunition, could offer only limited counter-fire. Task Force Faith suffered hundreds of additional casualties, and commanders knew the battered unit could not endure another assault of such intensity. Unlike previous nights, the enemy did not withdraw at first light but remained close, keeping up mortar and small-arms fire, while aid stations buckled under the mounting tide of wounded—far beyond the diminished medical staff's capacity to treat.

Convinced the task force could not survive another assault, Lieutenant Colonel Faith ordered immediate preparations for a breakout to Hagaru-ri, directing artillery batteries and the Heavy Mortar Company to expend all remaining ammunition before destroying their weapons. All nonessential equipment—trucks, radios, and vehicles that couldn't carry wounded—was systematically destroyed with white phosphorus and thermite grenades, leaving the force to fight south with only small arms, limited anti-aircraft weapons, and Marine air support. Faith planned to move along the snow-covered road skirting Hill 1221 toward Hudong-ni, expecting support from the 31st Tank Company and rear command post there. However, in a controversial decision, both units had already been ordered to withdraw directly to Hagaru-ri on November 30—the same day General Barr informed Faith no reinforcements were coming. This miscommunication left Faith effectively on his own, tasked with leading his battered force and hundreds of wounded approximately ten miles south through entrenched Chinese positions to reach Hagaru-ri.

The breakout column departed with 22 vehicles carrying approximately 600 wounded, organized with the 1/32 Battalion in the lead, followed by the 57th Field Artillery and Heavy Mortar Company, then the trucks laden with casualties, and finally the 3/31 Battalion serving as rear guard. Almost immediately, the column came under withering fire from concealed Chinese positions along the ridgelines, but worse was yet to come. In a tragic and unfortunate incident, four Marine Corsair aircraft suddenly dove on the lead elements and struck them with napalm, the jellied gasoline erupting in sheets of flame across the road. The devastating friendly-fire strike caused immediate casualties among troops already under fire, destroyed vehicles, and threw the forward units into chaos just as the breakout was beginning.

The column pressed south until a destroyed bridge forced the convoy off the road and onto the exposed ice of the frozen reservoir to bypass the obstruction. Once back on the road, which curved around the far side of Hill 1221, Chinese forces unleashed devastating crossfire from the hill and surrounding heights. Recognizing the danger, Lieutenant Colonel Faith rallied several hundred men—including walking wounded who volunteered to fight—for a desperate assault up the steep slopes. Despite heavy casualties, they drove the Chinese from much of the hilltop, but the victory was fleeting: many exhausted survivors abandoned the column, striking out independently across the frozen reservoir. Amid the savage fighting, Lieutenant Colonel Faith was severely wounded by grenade fragments, leaving the task force without effective leadership at its most critical moment.

The convoy struggled forward, clearing roadblocks while Chinese forces renewed their attacks from the other side of Hill 1221 with devastating effect, methodically shredding what remained of the column. The battered remnants never reached Hudong-ni—the convoy ground to a halt short of the town as each successive ambush forced more trucks to be abandoned. With every attack, cohesion deteriorated as casualties mounted and the few remaining able-bodied soldiers lost all capacity to defend the convoy. Leadership had effectively collapsed, and soldiers saw no path forward except individual survival. As organized resistance disintegrated, individual soldiers and small groups scattered desperately—some fleeing across the frozen reservoir toward Marine positions in the south, others stumbling along the shoreline toward Hagaru-ri, abandoning equipment and wounded. The organized fighting strength of Task Force Faith had ceased to exist. Amid this final collapse, Lieutenant Colonel Faith died of his wounds in the cab of a truck.

This timeline captures the principal events of the five-day battle. The section that follows expands on these events, drawing on after-action reports, survivor accounts, and historical records to convey the full scale of the fighting and the conditions endured by Task Force MacLean/Faith.

To deepen our understanding of our father’s experience, I have drawn on Captain Richard Kitz’s seven-page personal statement throughout this narrative. As our father’s company commander, Captain Kitz provides the closest and most immediate firsthand account of what Dad faced during the battle. Readers who wish to review Captain Kitz’s statement in its original, unedited form may access it below.

In addition to Kitz's account, I was able to obtain multiple after-action reports, other personal statements and command orders from the National Archives. These official, declassified records offer essential firsthand detail and context. Where they illuminate events involving Company K or add clarity to our father’s experience, their accounts have been cited and integrated into the narrative that follows.

Five Days of Hell

The timeline above establishes the chronological framework of events. What follows is a more detailed examination of the battle, with particular focus on the experiences of Company K—our father's unit—and the broader tactical context necessary to understand how a well-equipped American regimental combat team was systematically destroyed in five days of fighting.

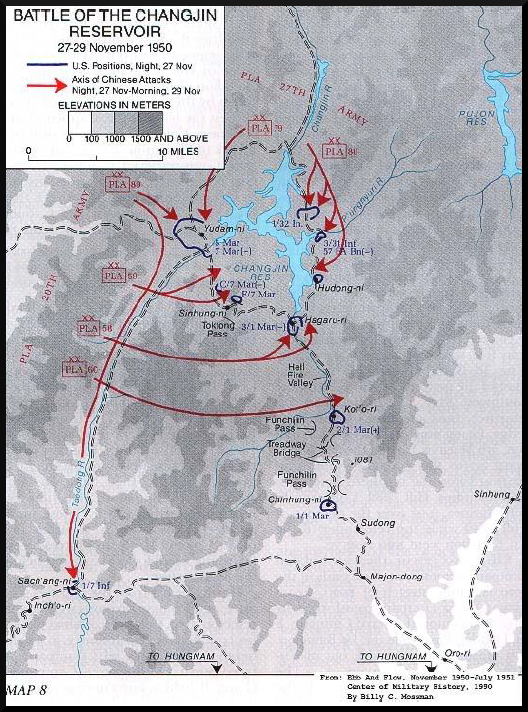

Initial Chinese Assault

The red arrows on the map below trace Chinese Communist Forces (CCF) attack routes, revealing the precarious position of American Marine and Army forces deployed around the Chosin Reservoir. By November 27, the CCF had achieved complete encirclement, seizing the dominant high ground on all sides with such stealth that their presence went largely undetected until the attacks began. Their operational plan was nothing less than the annihilation of the entire X Corps through coordinated, full-force assaults; the 1st Marine Division on the western shore and RCT-31 (the Army's 31st Regimental Combat Team) on the eastern side would be destroyed simultaneously. RCT-31 was a composite force of American infantry, artillery, and support units, reinforced with integrated Republic of Korea (ROK) soldiers who served in various capacities throughout the task force.

CCF Encirclement of X Corps and Attack Routes

Roy E. Appleman, “CCF Encirclement of X Corps” (Map 8), inEast of Chosin: Entrapment and Breakout in Korea, 1950 (College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 1987).

The Chosin Reservoir, roughly eight miles long, divided the American forces—Marines deployed on the western shore, RCT-31 on the eastern side—with only a single treacherous mountain road connecting each position to Hagaru-ri in the south. The Chinese strategy was designed for total annihilation: relentless nighttime attacks would pin the Americans in place, preventing coordination between the separated forces and making any organized breakout impossible. Even if RCT-31 attempted to fight its way south, the CCF planned to seal the trap by occupying Hill 1221, a commanding height that dominated the only escape route to Hagaru-ri, where the 1st Marine Division headquarters, a crude airstrip, and critical supply dumps represented the sole point of evacuation and resupply. To guarantee complete encirclement, Chinese forces would simultaneously thrust south of Hagaru-ri to sever the road at Koto-ri and beyond, cutting off the mountainous withdrawal route to the port at Hungnam and ensuring that no American unit—Marine or Army—could escape the reservoir alive.

Company K: Deployment at Chosin

The following account shifts from the strategic overview to ground level—to the specific experiences of Company K, our father's unit, during four nights of relentless Chinese assaults. Drawing from Captain Richard J. Kitz's after-action report and other sources, this narrative reveals the chaos, confusion, and raw terror that engulfed the 3/31st Battalion's positions during the first night of assaults when the CCF struck without warning in overwhelming force.

Company K had arrived at the Chosin Reservoir at approximately 1600 hours on November 27, immediately establishing defensive positions on the eastern side of the reservoir's northern inlet overlooking the bridge. Captain Kitz deployed his three rifle platoons across a broad defensive area:

- Two squads of the 1st Platoon, commanded by Lieutenant McFarland, were positioned on the trail east of the bridge.

- The 3rd Platoon held positions on a ridge line.

- The 2nd Platoon extended further down the ridge, connecting with the 3rd Platoon on one side and Company I's positions on the other.

- A weapons squad with one machine gun was stationed at the base of the ridge.

- A machine gun section from Company I covered the draw between positions.

Records do not indicate which of these three platoons or their squads our father was assigned to during the coming battle, so we cannot know his precise position on the defensive perimeter when the assault began. What is evident, though, is that he would have been positioned in front of the bridge or just east of the bridge along a ridge.

At approximately 1900 hours, Captain Kitz reported to the 3/31 Battalion command post, where Colonel Riley issued orders for a northward attack the following morning. These orders reflected Operations Order O-25, issued by Colonel MacLean that morning, which directed an aggressive attack north toward the Yalu River. The operational plan called for the 3/31 Battalion to seize Objective A and protect the regiment's eastern flank before continuing the northward advance. Company K was to advance along the ridge line while Company L moved north along the road, with Company I held in reserve. It was a routine briefing for what appeared to be a routine operation. None of them knew that within hours, the Chinese would launch a devastating surprise assault that would shatter their plans and nearly destroy the battalion.

First Night: November 27-28

At 2200 hours, the carefully laid plans for the next morning's attack became irrelevant. Chinese divisions launched their ferocious assault under cover of darkness against the 1/32nd perimeter to the north. The sound of bugles and shouting voices echoed across the frozen landscape as the CCF 80th and 81st Divisions moved to encircle Task Force MacLean's three deployment positions. On the eastern side of the inlet, CCF units had moved into position for a surprise, full frontal assault against Company K—our father's unit. Unknown to the Americans on all sides of the 3/31st's perimeter, they faced the full force of this initial onslaught.

Around 0100 hours, Captain Kitz heard intermittent gunfire and immediately called Lieutenant McFarland to determine its source. At 0130 hours on November 28, the sporadic firing suddenly intensified into a heavy coordinated attack against the 3/31st's positions. Official command reports record that the enemy broke through and overran Company K. As Kitz hurriedly put on his boots to investigate, the situation exploded into chaos. Heavy gunfire erupted at close range as the Chinese assault breached the perimeter and reached the company command post in the center. The CP itself was now under direct fire.

The sudden violence threw the rear area into complete disorder. Cooks emerged from their tents in confusion, and several ROK soldiers working in the kitchen area began to flee in panic. Captain Kitz ran approximately 50 yards to stop the retreating soldiers and attempted to rally them. As he worked to restore order, more men came streaming over a nearby rise—a mixture of ROK soldiers and American troops, all falling back under intense Chinese pressure.

Kitz attempted to organize a defensive line and get the men to return fire, but the situation had deteriorated beyond control. In the darkness, with muzzle flashes lighting the night and soldiers running in all directions, it became impossible to distinguish between retreating ROK troops and attacking Chinese forces. Friend and foe were intermixed in the chaos, making organized resistance nearly impossible. Close-in fighting resulted in Company K being caught between enemy and friendly forces, forcing the company to withdraw to the positions of A Battery, 57th Field Artillery Battalion. When A Battery ran out of ammunition firing direct fire into the advancing enemy, both Company K and A Battery withdrew together to B Battery's positions, where they consolidated with Company I. From these combined positions, the unit held the enemy attackers off until they withdrew at daylight. Adding to the confusion and casualties, the 57th Field Artillery's guns inadvertently fired into retreating American positions during the height of the assault.

At this critical moment, Lieutenant Simpson, the battalion communications officer, arrived and informed Kitz that Colonel Riley had been wounded and that all officers should report to the battalion command post. Fighting their way through Chinese soldiers who had infiltrated the area, Kitz and Simpson made their way down the road toward the CP. The scene they encountered was equally chaotic—the command post itself was under attack, with Chinese forces having penetrated deep into the American positions.

Throughout the night, Chinese forces attacked in waves. American defenders fought desperately, but the extreme cold compounded every challenge. Weapons jammed from the freezing temperatures. Wounded men faced a stark choice between remaining in position where they might freeze to death or attempting to reach aid stations through areas crawling with enemy soldiers. Many who were wounded during the night attacks died from exposure before they could receive medical treatment. We know Dad was not wounded during the battle, suggesting he fought at close quarters until overwhelmed and was likely one of those forced to retreat to the 57th FAB's position to survive.

Captain Kitz spent the remainder of the night attempting to reorganize Company K's scattered survivors and establish a cohesive defensive position. In the darkness, this proved nearly impossible. Small groups of soldiers fought isolated battles across the ridgelines and draws. Some units maintained their positions; others fell back in disorder. By dawn on November 28, Company K—which had arrived at the reservoir the previous afternoon as a fully functional infantry company—had lost approximately half its strength and existed only as scattered fragments desperately trying to survive until daylight.

The chaos of the first night's fighting is reflected in the 3rd Battalion's operations log. At 0400 hours on November 28, the battalion reported it had lost contact with Company K. Contact was recovered fifteen minutes later at 0415 hours. This brief notation in the official record captures the confusion and fragmentation that characterized the defensive battle—even battalion headquarters temporarily lost track of entire companies in the darkness and disorder of the Chinese assault.

Catastrophic Losses and Desperate Defense

The first night's fighting devastated Company K's leadership structure. When Captain Kitz reached the battalion command post, he learned the full extent of the disaster. Lieutenant McFarland and virtually his entire 1st Platoon—approximately 50 men—had been overrun and destroyed. The 2nd Platoon commander, Lieutenant Everest, was killed in action. Lieutenant Smith of the 3rd Platoon was seriously wounded. Of Company K's four officers, only Captain Kitz and Lieutenant McFarland remained unwounded and capable of command. Unfortunately, we do not know which platoon Dad was assigned to, but this description of the chaotic scene reveals the desperation he must have faced during this massive, unexpected onslaught.

The battalion's situation was equally grim. Colonel Riley, though wounded, maintained command. Lieutenant Colonel Embree, commanding officer of the 57th Field Artillery Battalion, was also among the wounded. The Chinese assault had achieved devastating effect across all the task force positions. The defensive perimeters that had seemed adequate in daylight proved woefully insufficient against the coordinated night attack by forces that held every advantage of terrain, numbers, and surprise. The reason Company K received no immediate artillery support became clear: Batteries A and B of the 57th Field Artillery were simultaneously being overrun and fighting for their own survival, unable to respond to fire mission requests from the infantry companies.

Reference: 31st RCT Journal (S-1 Log), Untaek, Korea, pages 56–59, November–December 1950;, declassified under Authority NND 745074, National Archives; Vallowe, Ray C., What History Failed to Record, 2013, pp. 118-120.

Day Two: November 28, 1950

Dawn on November 28 revealed the full extent of the previous night's disaster. The three company positions in the RCT-31 perimeter had been completely surprised, overwhelmed, and forced to endure an unrelenting, intense siege, with Chinese forces occupying commanding positions on the surrounding hills. The task force had suffered catastrophic casualties, lost much of its equipment, and seen its command structure severely damaged. The 1/32 Battalion alone had suffered more than 100 killed and another 100 wounded. The 3/31 Battalion and the 57th Field Artillery Battalion also sustained heavy casualties, and the already reduced personnel of the 31st Medical Company were virtually destroyed. Any hope of continuing the northward attack had evaporated. The only remaining question was survival itself.

Morning Assessment and Attempts to Reorganize

As daylight broke, Captain Kitz surveyed what remained of Company K. The scene was devastating. Bodies of American and Chinese soldiers lay scattered across the frozen ground. Equipment was strewn everywhere—abandoned weapons, overturned vehicles, destroyed tents. Of the company that had numbered over 150 men the previous day, fewer than half remained combat-effective. Many were wounded. All were exhausted from the night's fighting and the bone-numbing cold.

Kitz established a command post in a partially destroyed building and began the grim task of reorganizing his company. He consolidated the survivors of the three rifle platoons into two composite platoons, redistributed ammunition and weapons, and attempted to establish a coherent defensive perimeter. The men dug in as best they could—the frozen ground made proper entrenchment nearly impossible, so they piled rocks and used frozen corpses to create crude breastworks.

Throughout the morning, sporadic Chinese fire continued from the surrounding hills. Occasionally, a sniper would find a target. More often, mortar rounds fell into the perimeter, causing further casualties and keeping the defenders constantly on edge. American artillery attempted to suppress the Chinese positions, but ammunition was already running low, and overland resupply seemed unlikely given the Chinese control of the surrounding terrain.

Company K had been decimated in the first night's assault. Dad, serving in one of the rifle platoons, survived the chaos—the close fighting, the desperate withdrawal under fire toward the artillery positions, and the long, tense wait for dawn. It is possible during this first night, when his position was completely overrun, that he experienced one of the most harrowing moments of the battle: playing dead while enemy soldiers prodded him with rifle butts as they moved through the area checking bodies.

This survival tactic, as harrowing as it sounds, was used by other survivors as well. One soldier later recounted keeping himself stiff when the enemy probed about, only to have a Chinese soldier discover he was still alive by feeling his body heat. The soldier was beaten with rifle butts and thrown onto a heap of dead bodies, where he was left for dead. He ultimately survived by crawling across the frozen reservoir to Marine lines. Dad's experience was not unique—it was a desperate measure taken by men fighting for survival in the most extreme circumstances. This was only the beginning of a five-day ordeal that would drive these men to the outer limits of human endurance.

Almond's Visit and Misjudgment: November 28

In a surreal moment amid the chaos, Major General Almond arrived by helicopter at the 1/32 Battalion's command post that morning, accompanied by his aide, First Lieutenant Alexander Haig. Both Colonel MacLean and Lieutenant Colonel Faith were present. Despite overwhelming evidence of massive Chinese intervention, Almond exhorted the soldiers to stick with the original order to begin the northern offensive.

Before departing, Almond awarded Lieutenant Colonel Faith the Silver Star for gallantry. Yet the gesture rang hollow, as he offered no relief from the desperate circumstances and continued to insist on an attack. Disillusioned and frustrated by his commander's lack of understanding, Faith tossed the Silver Star into the snow after Almond's departure.

Almond could not have been more mistaken. The so-called "remnants" were, in reality, tens of thousands of fresh, well-coordinated Chinese troops who had already encircled much of the task force. Almond's dismissive attitude and failure to grasp the scale of the Chinese intervention left Task Force MacLean/Faith dangerously exposed and woefully unprepared for the onslaught that had already begun.

Second Night: November 28-29

Any belief that the enemy consisted only of scattered remnants was catastrophically wrong. The second night of fighting began before darkness had fully settled. As Chinese forces pressed in along the perimeter, a machine-gun position held by Company K was overrun, severing communications almost immediately. By that point, Captain Kitz had fewer than sixty men remaining in the company. With radios destroyed and command and control fractured, Company K fought in near isolation.

Throughout the night, Chinese forces attacked from every direction. The pressure was constant and unrelenting. The 57th Field Artillery's 40 mm guns played a critical role in preventing a collapse of the line, cutting down attackers advancing around nearby structures. The effects of the fire were visible by the light of burning buildings as wave after wave pressed closer to the perimeter.

The fighting continued without pause until morning. Although no decisive breakthrough occurred, the cost was severe. Company K and Company L suffered such heavy casualties that the two units were forced to physically merge into a single defensive position. Ammunition dwindled, exhaustion set in, and the perimeter grew steadily thinner.

Recognizing the exposed position of the 1/32 Battalion to the north, Colonel MacLean ordered a withdrawal south to the 3/31 perimeter in the early morning hours of November 29, at approximately 0200 hours. He directed that all weapons and wounded be brought along. Unneeded vehicles were disabled, wounded were loaded into trucks, and the movement was set to begin at 0500 hours when daylight came and Marine aircraft could provide support for the withdrawal.

Death of Colonel MacLean: Dawn, November 29

At first light, the 1/32 Battalion began its fighting withdrawal to the 3/31 perimeter. The movement took place under intense enemy fire. When the lead elements reached the 3/31 perimeter, they found it still under heavy attack. Lieutenant Colonel Faith led a party of men that successfully drove the CCF off the bridge and cleared the area in front of Company K's position. Colonel MacLean then came forward in his jeep when he spotted a column of troops approaching whom he believed was his long-overdue 2/31 Battalion. However, the troops were actually Chinese Communist Forces who were positioned along the shoreline near the bridge.

As MacLean advanced across the ice towards the soldiers he mistakenly thought were Americans, the CCF soldiers suddenly unleashed a burst of gunfire, striking him multiple times. His men could only watch in horror as enemy soldiers seized the wounded colonel and dragged him into the surrounding brush. MacLean would die from his injuries four days later while in Chinese captivity, on December 3, becoming the second—and ultimately the last—American regimental commander killed during the Korean War.

Given that Company K held the defensive sector directly opposite the bridge, it is plausible that our father witnessed—or at least heard—the chaotic scene in which the colonel was captured. At that moment, with the capture and subsequent death of Colonel MacLean, RCT-31's unofficial designation changed from Task Force MacLean to Task Force Faith.

Faith Takes Command and Consolidation: November 29, Daytime

Once inside the perimeter, Lieutenant Colonel Faith surveyed the carnage. Hundreds of American and CCF dead littered the ground. The 3/31 Battalion had suffered over 300 casualties. Company L had been completely destroyed as a fighting unit, with the few survivors merged into Company K. With MacLean gone, Lieutenant Colonel Faith assumed command of the regiment and worked to strengthen the perimeter, consolidating the task force into one defensive position in preparation for intensified Chinese attacks.

Marine air controller Captain Stamford, attached to RCT-31 to coordinate air support throughout the battle, radioed for close air support and coordinated airdrops of urgently needed supplies and ammunition. Throughout the day, Marine aircraft provided close air support against Chinese positions and conducted supply drops. However, many bundles landed outside the perimeter and fell into enemy hands, including critically needed artillery ammunition. Meanwhile, following Colonel MacLean's capture, Lieutenant Colonel Faith dispatched search parties to locate him, but all efforts proved unsuccessful.

For the men of Company K and the rest of Task Force Faith, this period was a test of endurance. The extreme cold continued to take its toll—frostbite casualties mounted, weapons continued to malfunction, and the wounded suffered terribly. Medical personnel, already severely limited at the start of the battle, were virtually wiped out during the fighting, and medical supplies were running critically low. Morphine had frozen solid and was useless. Plasma couldn't be administered in the freezing temperatures. Many wounded men simply died from exposure.

Captain Kitz spent his time moving among his men, checking their positions, ensuring they stayed awake (falling asleep in such cold could be fatal), and maintaining morale as best he could. By this point, Company K—now including the survivors of Company L—numbered fewer than sixty combat-effective soldiers. The men displayed remarkable courage and discipline. Despite exhaustion, casualties, and the seeming hopelessness of their situation, they maintained their positions and returned fire when Chinese forces approached.

Third Night: November 29-30

While the nights of November 27-28 and November 28-29 saw fierce, coordinated Chinese assaults against Task Force Faith and the Marine positions on the western side of the reservoir, the night of November 29-30 was comparatively quiet. After two nights of intense assaults failed to break the American defenses, Chinese forces ceased their major offensive attacks that third night, focusing instead on consolidation and preparation rather than launching another wave of coordinated assaults. The U.S. perimeter remained intact, with only sporadic small-arms fire and occasional mortar rounds reported rather than full-scale attacks.

Some Chinese units conducted minor probes against key approaches to the American perimeter, but by dawn the lines held and major action had subsided. This lull likely reflected a calculated pause by Chinese commanders, who withdrew briefly to regroup and bring forward additional reinforcements, including heavy mortars and light artillery, for the next wave. After nights of costly frontal assaults against American positions, the CCF had suffered staggering losses and needed to reorganize before the campaign's decisive, final phases. The pause was uneasy, a momentary breath before the storm that neither side could truly escape.

Although large-scale attacks were absent, the defenders still faced extreme hardships. Temperatures remained near −30°F, heavy snow continued to fall, and U.S. units stayed cut off, relying on hazardous aerial resupply during the daylight hours for critically low ammunition and food.

Decision to Withdraw: November 30, Daytime

On November 30, Major General David Barr, commander of the 7th Infantry Division, arrived by helicopter with grim news for Lieutenant Colonel Faith. All X Corps units, including Task Force Faith, were now placed under under Marine operational control and were to prepare for withdrawal to Hagaru-ri. However, both Barr and Marine General Oliver P. Smith agreed that the Marines were in no position to send relief forces to aid the soldiers on the east side of the reservoir. While the Marines would be able to continue to furnish air support, Task Force Faith would have to fight its way back on their own—a daunting prospect compounded by the nearly 600 wounded they were carrying.

Fourth Night: November 30-December 1

On the evening of November 30, around 2000 hours, Chinese Communist Forces launched their fourth successive night assault. This attack was far more powerful and sustained than tose of previous nights, reinforced by heavy mortar and light artillery fire that rained down on the perimeter throughout the long, bitter night. Wave after wave of Chinese troops pressed against Task Force Faith's positions. Only a few managed to penetrate the defenses, and those were quickly cut down. Despite inflicting severe losses on the enemy, Task Force Faith suffered heavy casualties, leading commanders to realize another major assault could not be endured.

From Company K's perspective, the night was unrelenting. Captain Kitz later described the intensity: the attack began early in the evening and continued without pause through the night. Chinese forces unleashed a torrent of fire—120 mm mortars supported by a mix of large, medium, and light calibers—alongside relentless small-arms and machine-gun fire. The artillery was almost out of ammunition and couldn't fire as much as needed. The .50 caliber machine guns were short of ammunition, as were the 40mm guns. Soldiers firing M-1 rifles had to conserve ammunition. Hand grenades were in short supply. As Kitz bluntly stated in his statement, "We just didn't have what we needed."

Unlike previous nights when Chinese forces withdrew at dawn to avoid Marine air attacks, the enemy changed tactics this time. As Kitz observed, "this time instead of withdrawing in the morning as they had been doing, they stayed right down there in the low ground with us, stayed right down there in the perimeter and were getting alot of grazing fire. Got alot of people hit too at that time." This tactical shift—maintaining pressure throughout daylight hours—was particularly ominous. The sustained attacks and continued enemy presence overwhelmed the aid station, which Kitz described as being "in tough shape," leaving a flood of wounded men in desperate need of care. For Company K and the other units, the night of November 30 marked the peak of intensity before the breakout attempt, a test of endurance, courage, and cohesion under extreme winter conditions.

Reference: Vallowe, Ray C., What History Failed to Record, 2013, pp. 157-158 (quoting Captain Robert J. Kitz's personal statement).

The Decision to Break Out

Following the fourth night of sustained enemy attacks, Lieutenant Colonel Faith recognized that Task Force Faith could not survive in its current position. Ammunition was critically low. Casualties mounted by the hour. Medical supplies were exhausted. The cold continued to disable men and equipment alike. No relief force was coming—the Marines on the western shore were fighting their own desperate battle and could offer no assistance.

Faith made the fateful decision to attempt a breakout to the south, fighting through the Chinese encirclement to reach Hagaru-ri, approximately twelve miles away. This was the only remaining option. Staying in place meant slow destruction. Attempting to break out to the north, toward the Chinese border, was impossible. The only hope lay in fighting south along the single road to Hagaru-ri.

Preparation for Breakout

Task Force Faith prepared for the breakout attempt. All remaining supplies were loaded onto vehicles. The wounded—by now numbering in the hundreds—were placed in trucks. Units were reorganized into march columns. Captain Kitz consolidated Company K's remaining effectives and prepared them for what everyone knew would be a desperate fight.

The plan called for a column of vehicles carrying the wounded to proceed down the road, with infantry units providing security on the flanks. Marine and Navy aircraft would provide close air support, attacking Chinese positions along the route. The artillery batteries and Heavy Mortar Company were ordered to fire all remaining ammunition before the breakout, then destroy their weapons to prevent capture. It was a sound tactical plan under the circumstances, but it depended on maintaining unit cohesion and momentum during the withdrawal—qualities that would prove impossible to sustain once the column arrived at Hill 1221 and came under intense fire from all sides.

The Breakout Attempt: December 1, 1950

By December 1, 1950, American forces were on the brink of collapse. Ammunition stocks were critically low, and more than half of the troops were either killed or wounded, including a disproportionate number of senior leaders. Lieutenant Colonel Faith had already made the decision that a desperate southward breakout toward the Marine lines at Hagaru-ri was the only option. At 1100 hours, the formal order arrived from the commander of the 1st Marine Division. Faith gathered his remaining officers and set a departure time of 1300 hours. Only the bare essentials were kept: enough vehicles to evacuate roughly 600 wounded soldiers and minimal personal gear. All other materiel—including trucks, radios, and artillery howitzers—was deliberately destroyed on site after firing their final rounds, to prevent any of it from falling into enemy hands.

Column Formation and Early Movement

The breakout column was led by the 1/32 Battalion, now commanded by Major Crosby P. Miller. Behind it followed the 57th Field Artillery Battalion, the Heavy Mortar Company, and the 3/31 Battalion—which included Company K—bringing up the rear as the rear guard. This was a particularly dangerous assignment, as rear guard units typically bear the brunt of pursuing enemy attacks. At 1300 hours, the convoy departed, spearheaded by a twin-mounted 40 mm gun vehicle.

The convoy—carrying the wounded soldiers crammed into just twenty-two trucks—trudged south along the snow-slick gravel road that clung to the reservoir's edge. Enemy fire swept from the surrounding hills, forcing the men to scramble for any bit of cover they could find. In his after-action report, Captain Kitz, commander of Company K, noted that maintaining any coherent formation was virtually impossible; the troops were compelled to huddle behind the trucks for protection and, whenever the fire intensified, to dash toward the reservoir's shoreline for additional shelter. Dad, as one of Company K's riflemen in the rear guard, would have experienced the confusion, fear, and relentless pressure Kitz recounted.

Lieutenant Colonel Faith kept the breakout column tightly packed, limiting the convoy to those twenty-two vehicles to transport the wounded. Marine F4U Corsairs and Navy F7F twin-engine fighters delivered vital close-air support, strafing and bombing Chinese positions as the heavily burdened American column inched southward along the gravel road on the eastern shore of the Chosin Reservoir.

Friendly Fire Incident

Shortly after the column had moved out, fire erupted from concealed Chinese positions, tearing into the lead troops. In an effort to protect the convoy, four Marine pilots misjudged their napalm runs, striking the Americans instead of the enemy. Flames consumed several soldiers, killing them instantly and throwing the forward companies into chaos as they scrambled blindly, fleeing the very air support meant to protect them.

The aftermath was horrific. Survivors had to navigate around burning trucks while loading men who were still alive but terribly burned onto other trucks. As one witness described it, there was "really nothing any one can do for them at this point." The napalm incident, though acknowledged as an honest error—the canisters were simply dropped short on the leading force—had what survivors described as "utter desolation on all concerned." The psychological impact was immediate and devastating. The accidental napalm strike dealt a crushing blow to morale across the task force.

After briefly rallying his men, Lieutenant Colonel Faith pressed the column forward, moving past Chinese fire teams. Enemy positions pressed as close as 50-75 yards, making organized withdrawal nearly impossible. The 1/32 Battalion, tasked with leading the column, was repeatedly targeted. Roadblocks at multiple points forced the troops to move onto the ice of the reservoir, creating new hazards: sections of ice gave way under the weight of men and vehicles, plunging soldiers into freezing water. Some managed to climb out, while others did not. Captain Kitz himself fell through but survived. These trials highlighted the extreme peril of the breakout, as the troops battled both the enemy and the unforgiving terrain simultaneously.

Reference: Vallowe, Ray C., What History Failed to Record, 2013, pp. 168, 252.

As the convoy pressed forward, small groups of company officers—including Kitz and several artillery officers—rallied stragglers and spearheaded assaults on three key roadblocks along the route. We have no idea if Dad was part of these efforts, but since he wasn't wounded, it seems likely he would have participated with Kitz in these clearing actions. Their decisive efforts drove the column forward and allowed the vehicles to resume movement, offering the only chance to keep the breakout alive.

The Assault on Hill 1221

By 1700 hours, all ammunition for the artillery guns was exhausted. The task force now had only small arms, a few anti-aircraft weapons, and Marine air support—the artillery that had been critical to their defense was gone. The battered column ground to a halt as it approached Hill 1221, a commanding height that dominated the gravel road below. One battalion from the Chinese 242nd Regiment had established a strong defensive position on the hill and a roadblock at its base, blocking Faith's retreat. Well-established roadblocks and a damaged bridge north of the crest made any further advance impossible without first clearing the position.

Chinese small-arms and machine-gun fire raked the road from the heights, destroying vehicles and pinning down troops in the open. Casualties among officers and noncommissioned leaders had already begun to fracture unit cohesion, and the convoy risked complete destruction if it remained trapped beneath the hill.

Recognizing that the only hope of surviving was a direct attack on Hill 1221, Faith gathered his men together, even the wounded who could hold a rifle, and ordered them to take the hill. In a desperate assault, several units attacked Hill 1221 trying to clear it. Despite exhaustion, brutal cold, and mounting losses under intense fire, these troops succeeded in driving Chinese forces from portions of the hill late in the afternoon. During the assault, Faith was wounded when a grenade exploded near him, but he continued to lead his men forward.

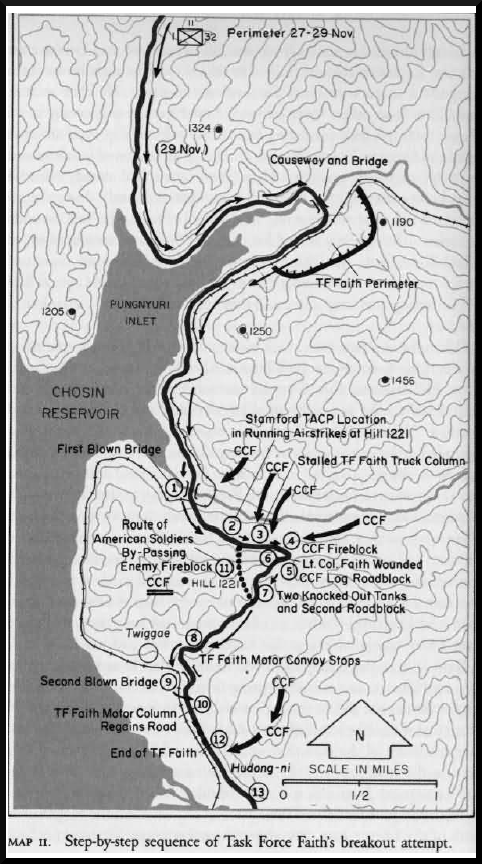

The map below illustrates the sequence of events during the hill assault, showing the path where Faith attacked the CCF and marking the spot where Faith was wounded and the location where he later succumbed to his injuries. According to Kitz's account, he was part of this attack, so it is possible our father was engaged in retaking this hill to allow the convoy to continue forward.

The Breakout Route and Hill 1221, December 1, 1950

Roy E. Appleman, The Breakout Route” (Map 11), inEast of Chosin: Entrapment and Breakout in Korea, 1950 (College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 1987).

The assault came at a severe cost. Most critically, many men who rushed up the hill and helped clear Chinese positions did not return to the column. Instead, disoriented and scattered, they continued over the hill's far side and descended independently, heading south across the frozen Chosin Reservoir toward Marine positions at Hagaru-ri. This mass departure stripped the column of desperately needed combat strength at the very moment when cohesion was most critical. The partial seizure of Hill 1221 enabled what remained of the column to break through the immediate roadblock and resume the march south as darkness fell, but the force was now dangerously weakened and increasingly fragmented.

The Hudong-ni Revelation: Abandoned and Alone

As Task Force Faith fought its way through multiple roadblocks, the survivors clung to one critical hope: that they would find support at Hudong-ni, just four miles to the south. Throughout the ordeal, the soldiers believed that the 31st Tank Company, the rear command post, service companies, ammunition dumps, and ration supplies all remained at Hudong-ni, ready to provide assistance once they reached the town. This belief sustained them through the desperate fighting—they were not alone; help was just ahead.

But when the remnants of the column finally approached Hudong-ni after dark, they encountered a devastating reality. As one survivor later described it: "No rear guard, no tank force or service companies, no ammo dump, no supplies of any kind-and no more unit order-it all unraveled here." Unknown to Faith and his men, at 1600 hours on November 30—before the breakout even began—both the 31st Tank Company and the RCT-31 rear command post had received orders to withdraw from Hudong-ni to Hagaru-ri. The tank company had reached Hagaru-ri by 1730 hours on November 30 and was immediately attached to the 1st Marine Division's perimeter defense.

The men of Task Force Faith had been fighting toward a rear guard that no longer existed. This withdrawal was never communicated to Lieutenant Colonel Faith, who continued to believe throughout December 1 that support awaited at Hudong-ni. The sad reality, as survivors later learned, was that those men who forfeited their lives on the midnight and early morning of December 1-2 never knew that the force they expected to find had been withdrawn on orders from outside their division command. This information remained classified as "Secret" and was deliberately hidden for forty years. Had this been known at the time, the fate of Task Force Faith—and the hundreds who died believing help was just miles away—might have been regarded very differently in history.

Reference: Vallowe, Ray C., What History Failed to Record, 2013, pp. 147, 168.

The Final Collapse

With Marine air cover withdrawn for the night, the column struggled forward in darkness. The convoy navigated past the wreckage of charred tanks from the 31st Tank Company's action on November 30, half-buried in the snow and narrowing the passage. As night closed in, Chinese infantry attacks grew increasingly bold. The unit, already fragmented from the Hill 1221 assault and battered by mounting casualties at every level of command, teetered on the brink of collapse.

During the fighting near Hill 1221, Lieutenant Colonel Faith was mortally wounded when a grenade exploded near him. His men placed him in the cab of a truck, though his wounds were fatal. The column pushed forward desperately, but Faith died as the convoy drew close to Hudong-ni. With his death and other senior officers killed, command disintegated completely. No one was left to assume overall command in the chaos.

As the convoy approached the outskirts of Hudong-ni, the Chinese renewed their attacks with devastating effect. The remnants of the column never reached Hudong-ni itself—the convoy ground to a halt short of the town. With every attack, more trucks had been abandoned. Each attack was as disheartening as it was deadly. The few remaining able-bodied soldiers could no longer maintain cohesion. The breakout attempt had failed. Individual soldiers and small groups scattered, many fleeing across the frozen reservoir toward the west, others moving along the shoreline toward Hagaru-ri. The organized fighting strength of Task Force Faith had ceased to exist.

Lieutenant Colonel Anderson, who had been the acting commander of the rear CP at Hudong-ni before withdrawing to Hagaru-ri on November 30, tracked the breakout convoy's progress through artillery radio relay and liaison aircraft observation. He later reported that the convoy of trucks 'were able to work the vehicles out just about as far as the school house, at which place they were definitely stopped. Enemy counter-measures broke them up into small groups. They were running short and, in some cases, completely out of ammunition.'

Beginning on the night of December 1, a few hours after the assault on Hill 1221 and continuing through the night and into December 2, small groups and isolated individuals began straggling into the Marine perimeter at Hagaru-ri. As Anderson observed, “They did not come in tactical groupings or sizeable units. They came in more as individuals. By far the largest number of people that came in early were the ROK enlisted men.” Nearly all survivors arrived without their weapons and equipment—a circumstance later used, unjustly, to brand them as cowards. In reality, a rifle without ammunition was more of a hindrance than a help when struggling across frozen terrain, particularly for the wounded and the severely frostbitten.

Reference: Lieutenant Colonel Anderson, Report on Operations, 31st Infantry,undated interview transcript [circa: December 1950-March 1951], National Archives.

Company K: Disintegration and Escape

For Company K, the final hours defy precise reconstruction. Command had disintegrated in the chaos, and the surviving accounts are scattered and incomplete. Even so, the available evidence establishes several points with reasonable certainty. ithout senior leadership, Company K, like the rest of Task Force Faith, ceased to function as an organized unit during the fighting on Hill 1221 and the subsequent breakdown near Hudong-ni. Captain Kitz’s after-action report ends with the destruction of the convoy, noting that he and as many as 210 others “took off over the ice for Hagaru-ri” at 1800 hours. He reached the Marine perimeter at Hagaru-ri around midnight. The timing of that movement strongly indicates those with him were among the last survivors to disengage from the convoy before its final destruction.

Kitz further states that the “convoy of trucks was surrounded and trapped and unable to advance further,” a description that clearly corresponds to the point at which the column was halted short of Hudong-ni. Whether my father was part of Kitz’s escape cannot be determined with certainty. What can be said is that, as a member of Company K, he was most likely present during those final hours and endured the same fighting, confusion, and collapse that Kitz describes.

Of the approximately 3,200 men of Task Force Faith who had defended the perimeter—including roughly 2,500 Americans and 700 ROK soldiers—the breakout attempt on December 1 involved an estimated 600 wounded loaded onto vehicles and perhaps 500 able-bodied troops still capable of fighting. Only 385 able-bodied men ultimately reached Marine positions at Hagaru-ri. Some lightly wounded soldiers escaped on foot across the frozen reservoir or along the road, moving individually or in small, fragmented groups. No trucks carrying wounded succeeded in breaking through; the vast majority of the injured were killed or captured when the column was destroyed. For Task Force Faith, the breakout ended in death, capture, or desperate individual escapes across the frozen mountains.